First-time parents don’t usually step into their new role with a pre-planned roadmap of their preferred parenting style. They’ve read articles and maybe even books about parenting approaches. They’ve seen ways other people interact with their children and bookmarked them for avoidance or emulation. They’ve also already received a lot of parenting advice from friends and relatives. But on that first day as parents, they’re not focused on parenting style. They are caught up in the excitement and exhaustion that come with holding, dressing, feeding, and changing a newborn, all while hoping for a little bit of sleep.

As time passes, they may ask questions about parenting styles as they consider their approach. There are many options to consider. A quick internet search results in a word salad of styles from classics like authoritarian and permissive to more modern terms like attachment, free-range, helicopter, tiger, snowplow, lawnmower, gentle, mindful, slow, and conscious. How are parents supposed to navigate this mix of terms, much less decide what is right for their family?

The first chapter of my dissertation and upcoming book dives deeply into the science of parenting and parenting styles over the past sixty years. The book will be available in a few months. In the interim, this essay gives a sneak-peek summary of some of the words and ideas that are the foundation of my conversations and writing about parenting.

The study and discussion of parenting styles began in the 1960s by Diana Baumrind, a psychologist who devoted her professional career to defining and researching different parenting approaches and their outcomes. I base my approach to parenting styles heavily on her work and am indebted to her for pioneering this field. However, some of her terminology is confusing or challenging to explain to parents in 2025. I use alternative words and explanations that are easier for today’s parents to grasp to avoid that confusion. I cite much of the original research and explain my terminology updates in my upcoming book.

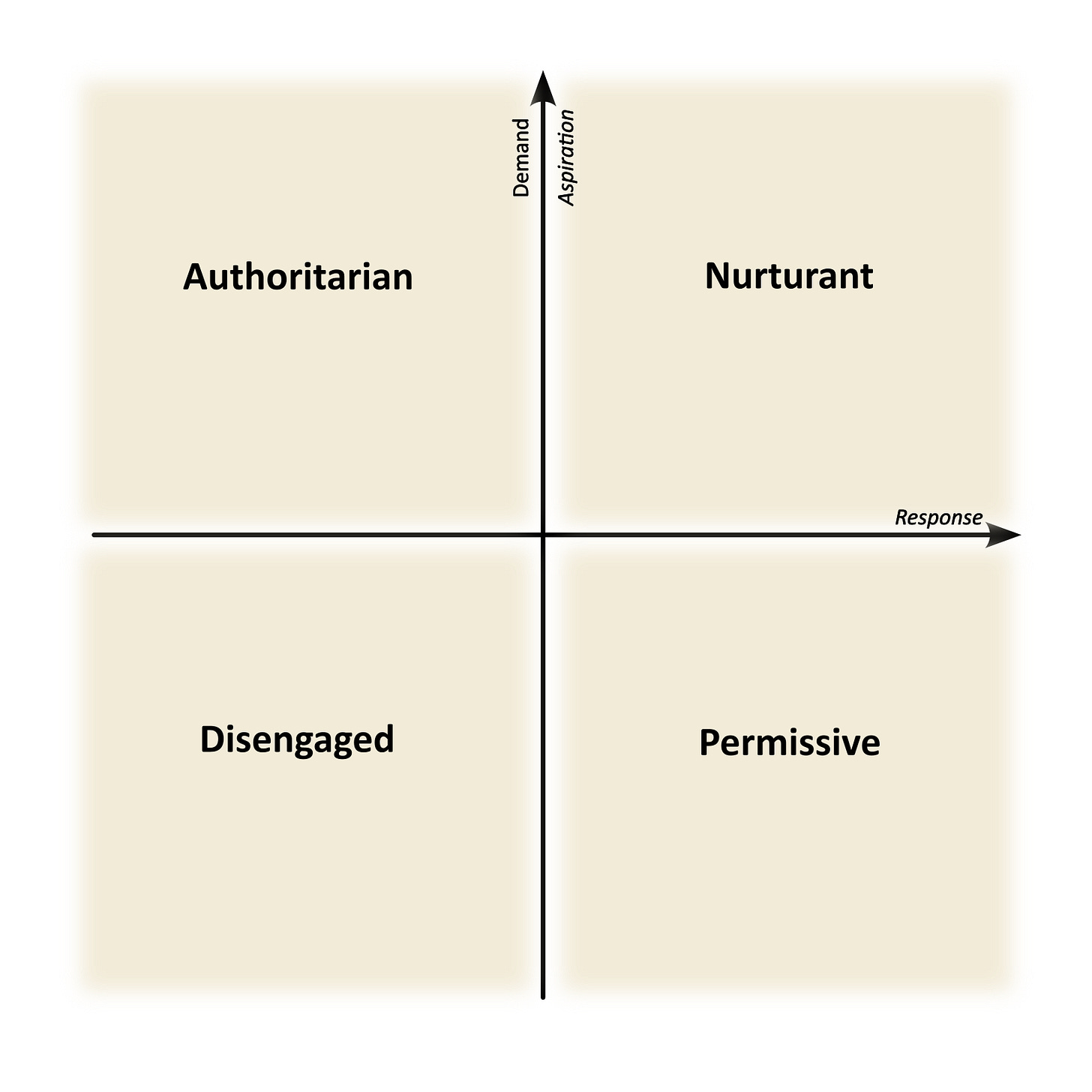

We can organize the classic parenting styles using an XY graph. The X-axis represents parents’ responsiveness to their children, and the Y-axis represents the degree of direction parents give their children. The two axes are not entirely independent. The Y-axis can represent parental demands or aspirations, depending on the style’s responsiveness. The axes of the graph create four quadrants that each represent one of the styles:

Authoritarian parents are highly demanding of their children and are not very responsive to them. They want their children to grow up as responsible societal contributors who follow the rules and respect authority. They attempt to control their children, molding them to a predetermined standard of conduct and evaluating them based on this standard. They value prompt obedience and will punish when the child’s will opposes their standard of conduct. Order, structure, hard work, and limitation of autonomy are valued. Dialogue between parents and children is discouraged because the child should accept the parent’s idea of what is right.

Children in authoritarian homes often become very good at obeying rules. However, because of their parents’ firm expectations, they may fail to develop self-discipline. They frequently learn that following rules and succeeding academically or athletically are markers of acceptance, and feel they need to earn love. They learn not to ask “Why?” because the answer is usually, “Because I said so.” These children may grow up as successful people in competitive environments, but are more likely to show aggressive behavior towards others, have social difficulties, and exhibit conduct problems or anxiety.

Permissive parents are very responsive to their children but provide little guidance regarding parental demands or aspirations. They highly value acceptance and affirmation of the child’s desires and actions and place few demands on their children concerning household responsibilities or behavior. They inconsistently enforce the rules that do exist. These parents emphasize their children’s freedom rather than responsibility and often seem more like a friend than a parent. They typically respond quickly to their children’s demands, sometimes with bribery, to avoid temper tantrums, crying, or other expressions of anger.

Children in permissive homes develop high self-esteem, but that can lead to self-centeredness and demandingness. A lack of paternal guidance and boundaries can also cause insecurity. They don’t need to ask, “Why?” because the answer is always, “Because you want to.” These children may grow up with a high level of self-confidence. However, their lack of parental direction may cause them to struggle with interpersonal skills and become stressed when their opinion is not valued over others.

Disengaged parents provide little direction and are unresponsive to their children. They rarely attend parenting seminars and do not typically engage with their child’s pediatrician, teachers, or coaches. Disengaged parents may also be considered absent parents. They may have passed away, been missing due to a divorce, or been distracted from parenting for various reasons. Disengaged parents are emotionally distant from their children and don’t interact with them. They provide no guidance, love, or affection toward their children.

Children who have disengaged parents develop self-reliance, but their lack of emotional connection with their parents can lead to low self-esteem and difficulties in relationships because of neediness. They don’t ask, “Why?” because the answer is, “I don’t care.” These children often develop self-reliance out of necessity. This potential benefit is outweighed by their inability to form healthy relationships later in life, which results from their lack of parental emotional connections.

Nurturant parents give their children high levels of guidance and responsiveness. They set high aspirations for their children but also hold them to high standards while giving affection, affirmation, and acceptance. When discipline is needed, its goal is restoration rather than retribution. Developmentally appropriate independence, creative thinking, and curiosity are valued. These parents listen to their children’s objections and suggestions and change their perspective in response to the children. They value cooperation, social responsibility, justice, concern for others, teamwork, empathy, and individual free will.

Children who grow up in nurturant families realize they are loved and are motivated to follow their parents’ lead because of their love and acceptance, rather than fear of consequences. They ask questions and make suggestions because their parents will answer their questions and consider their input. When asking, “Why?” their parents explain why a decision is best for the whole family. These children are more likely to have self-esteem and confidence. They relate to others well socially and emotionally. They develop tools to solve problems and improvise when facing new life challenges.

The question of which style is best naturally arises. Thankfully, we aren’t left to speculate. Several studies have examined data from many years, considering positive outcome measurements like cognitive competence, self-respect, and confidence. They also evaluated negative measurements like risk-taking behavior, lack of guilt, self-pity, excessive worry, and feelings of worthlessness. Based on these measurements, the styles are ranked from most to least beneficial: nurturant, disengaged, permissive, and authoritarian. Children whose parents actively lead and respond experience the best outcomes.

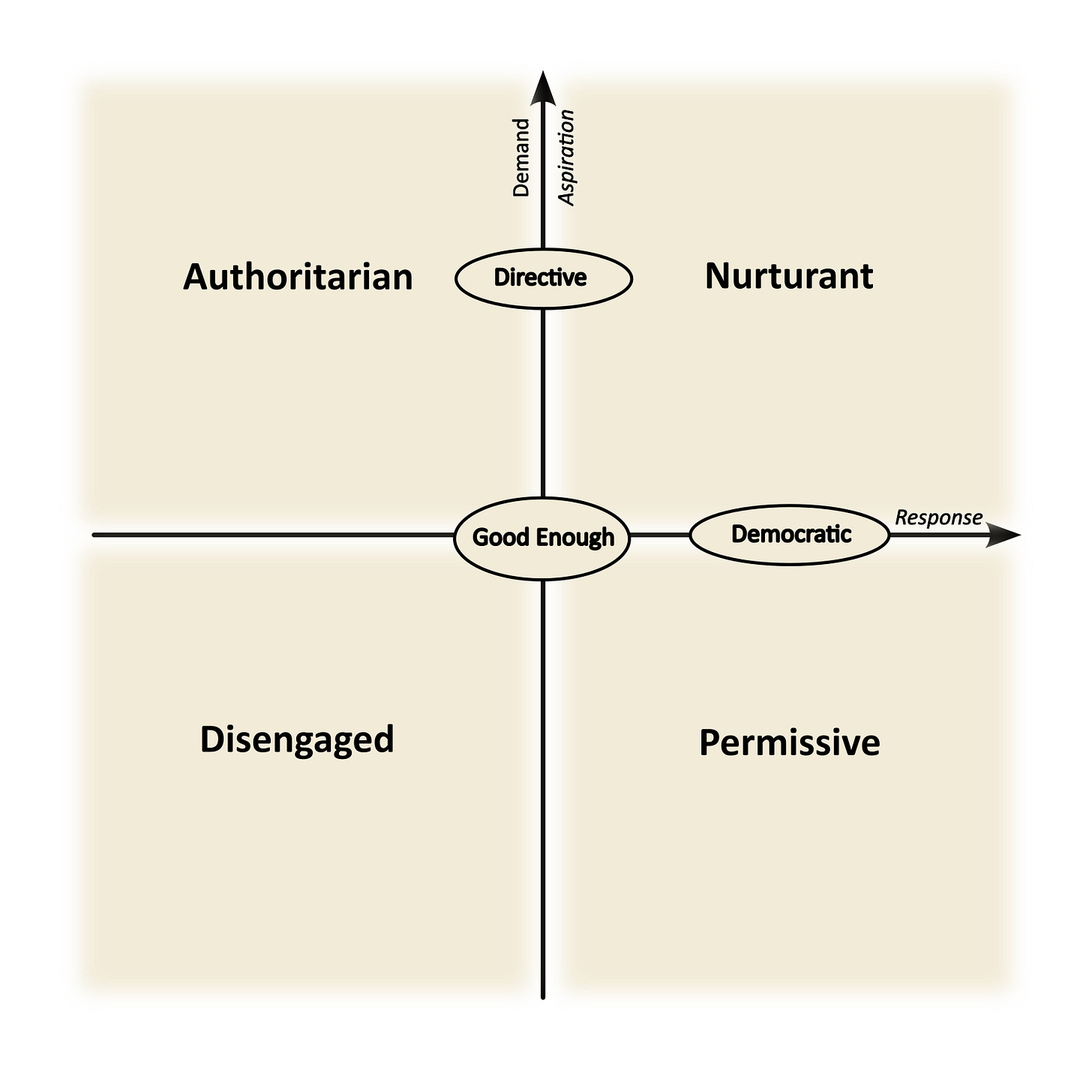

At the beginning of this essay, I listed far more styles than I have reviewed. What about the others? Three other styles have been well-studied and fit in this typology: directive, democratic, and good-enough. They sit at the borders between the other primary styles.

These styles recognize that parents don’t always reach the goal of being purely nurturant. They all lead to outcomes that are better than those of pure disengaged, permissive, and authoritarian parents.

Various other parenting styles have been described, including those listed at the beginning of this essay. I don’t discuss them as much because they haven’t been studied rigorously as the primary styles and are primarily subsets of the classic styles. However, they can help remind parents that certain aspects of a particular style should be avoided or emulated. Parenting techniques differ from styles in that they are specific tools parents use to achieve the goals of their style.

After all this science-based discussion about parenting styles and research, you may wonder where theology fits in. For people in religious traditions that think of God as a parent, their view of God’s parenting style is closely tied to their theology and affects their parenting. For example, a classical theist likely sees God as an authoritarian parent and may think they need to emulate this style with their children. Through my open and relational parenting model, I hope parents can see God as a nurturant parent and seek to emulate that style.

image: forge-flux ai